Who Is St. Francis?

St. Francis is the Founder of the Franciscan Order, born at Assisi in Umbria, in 1181 or 1182–the exact year is uncertain; he died there, 3 October, 1226.

His father, Pietro Bernardone, was a wealthy Assisian cloth merchant. Of his mother, Pica, little is known, but she is said to have belonged to a noble family of Provence. Francis was one of several children. The legend that he was born in a stable dates from the fifteenth century only, and appears to have originated in the desire of certain writers to make his life resemble that of Christ. At baptism the saint received the name of Giovanni, which his father afterwards altered to Francesco, through fondness it would seem for France, whither business had led him at the time of his son’s birth. In any case, since the child was renamed in infancy, the change can hardly have had anything to do with his aptitude for learning French, as some have thought.

Francis received some elementary instruction from the priests of St. George’s at Assisi, though he learned more perhaps in the school of the Troubadours, who were just then making for refinement in Italy. However this may be, he was not very studious, and his literary education remained incomplete. Although associated with his father in trade, he showed little liking for a merchant’s career, and his parents seemed to have indulged his every whim. Thomas of Celano, his first biographer, speaks in very severe terms of Francis’s youth. Certain it is that the saint’s early life gave no presage of the golden years that were to come. No one loved pleasure more than Francis; he had a ready wit, sang merrily, delighted in fine clothes and showy display. Handsome, gay, gallant, and courteous, he soon became the prime favourite among the young nobles of Assisi, the foremost in every feat of arms, the leader of the civil revels, the very king of frolic. But even at this time Francis showed an instinctive sympathy with the poor, and though he spent money lavishly, it still flowed in such channels as to attest a princely magnanimity of spirit.

When about twenty, Francis went out with the townsmen to fight the Perugians in one of the petty skirmishes so frequent at that time between the rival cities. The Assisians were defeated on this occasion, and Francis, being among those taken prisoners, was held captive for more than a year in Perugia. A low fever which he there contracted appears to have turned his thoughts to the things of eternity; at least the emptiness of the life he had been leading came to him during that long illness. With returning health, however, Francis’s eagerness after glory reawakened and his fancy wandered in search of victories; at length he resolved to embrace a military career, and circumstances seemed to favour his aspirations. A knight of Assisi was about to join “the gentle count,” Walter of Brienne, who was then in arms in the Neapolitan States against the emperor, and Francis arranged to accompany him. His biographers tell us that the night before Francis set forth he had a strange dream, in which he saw a vast hall hung with armour all marked with the Cross. “These,” said a voice, “are for you and your soldiers.”

“I know I shall be a great prince,” exclaimed Francis exultingly, as he started for Apulia. But a second illness arrested his course at Spoleto. There, we are told, Francis had another dream in which the same voice bade him turn back to Assisi. He did so at once. This was in 1205.

Although Francis still joined at times in the noisy revels of his former comrades, his changed demeanour plainly showed that his heart was no longer with them; a yearning for the life of the spirit had already possessed it. His companions twitted Francis on his absent-mindedness and asked if he were minded to be married.

“Yes,” he replied, “I am about to take a wife of surpassing fairness.”

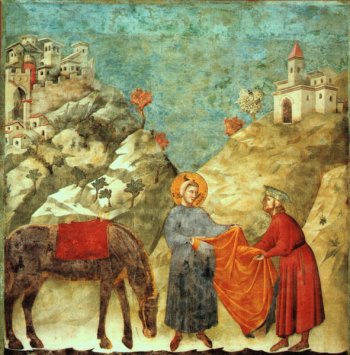

She was no other than Lady Poverty whom Dante and Giotto have wedded to his name, and whom even now he had begun to love. After a short period of uncertainty he began to seek in prayer and solitude the answer to his call; he had already given up his gay attire and wasteful ways. One day, while crossing the Umbrian plain on horseback, Francis unexpectedly drew near a poor leper. The sudden appearance of this repulsive object filled him with disgust and he instinctively retreated, but presently controlling his natural aversion he dismounted, embraced the unfortunate man, and gave him all the money he had. About the same time Francis made a pilgrimage to Rome. Pained at the miserly offerings he saw at the tomb of St. Peter, he emptied his purse thereon. Then, as if to put his fastidious nature to the test, he exchanged clothes with a tattered mendicant and stood for the rest of the day fasting among the horde of beggars at the door of the basilica.

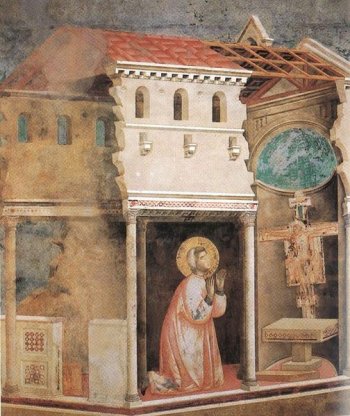

Not long after his return to Assisi, whilst Francis was praying before an ancient crucifix in the forsaken wayside chapel of St. Damian’s below the town, he heard a voice saying: “Go, Francis, and repair my house, which as you see is falling into ruin.” Taking this behest literally, as referring to the ruinous church wherein he knelt, Francis went to his father’s shop, impulsively bundled together a load of coloured drapery, and mounting his horse hastened to Foligno, then a mart of some importance, and there sold both horse and stuff to procure the money needful for the restoration of St. Damian’s. When, however, the poor priest who officiated there refused to receive the gold thus gotten, Francis flung it from him disdainfully.

The elder Bernardone, a most niggardly man, was incensed beyond measure at his son’s conduct, and Francis, to avert his father’s wrath, hid himself in a cave near St. Damian’s for a whole month. When he emerged from this place of concealment and returned to the town, emaciated with hunger and squalid with dirt, Francis was followed by a hooting rabble, pelted with mud and stones, and otherwise mocked as a madman. Finally, he was dragged home by his father, beaten, bound, and locked in a dark closet.

Freed by his mother during Bernardone’s absence, Francis returned at once to St. Damian’s, where he found a shelter with the officiating priest, but he was soon cited before the city consuls by his father. The latter, not content with having recovered the scattered gold from St. Damian’s, sought also to force his son to forego his inheritance. This Francis was only too eager to do; he declared, however, that since he had entered the service of God he was no longer under civil jurisdiction. Having therefore been taken before the bishop, Francis stripped himself of the very clothes he wore, and gave them to his father, saying: “Hitherto I have called you my father on earth; henceforth I desire to say only ‘Our Father who art in Heaven.'”

Then and there, as Dante sings, were solemnized Francis’s nuptials with his beloved spouse, the Lady Poverty, under which name, in the mystical language afterwards so familiar to him, he comprehended the total surrender of all worldly goods, honours, and privileges. And now Francis wandered forth into the hills behind Assisi, improvising hymns of praise as he went.

“I am the herald of the great King,” he declared in answer to some robbers, who thereupon despoiled him of all he had and threw him scornfully in a snow drift. Naked and half frozen, Francis crawled to a neighbouring monastery and there worked for a time as a scullion. At Gubbio, whither he went next, Francis obtained from a friend the cloak, girdle, and staff of a pilgrim as an alms. Returning to Assisi, he traversed the city begging stones for the restoration of St. Damian’s. These he carried to the old chapel, set in place himself, and so at length rebuilt it. In the same way Francis afterwards restored two other deserted chapels, St. Peter’s, some distance from the city, and St. Mary of the Angels, in the plain below it, at a spot called the Porziuncola. Meantime he redoubled his zeal in works of charity, more especially in nursing the lepers.

On a certain morning in 1208, probably 24 February, Francis was hearing Mass in the chapel of St. Mary of the Angels, near which he had then built himself a hut; the Gospel of the day told how the disciples of Christ were to possess neither gold nor silver, nor scrip for their journey, nor two coats, nor shoes, nor a staff, and that they were to exhort sinners to repentance and announce the Kingdom of God. Francis took these words as if spoken directly to himself, and so soon as Mass was over threw away the poor fragment left him of the world’s goods, his shoes, cloak, pilgrim staff, and empty wallet. At last he had found his vocation. Having obtained a coarse woolen tunic of “beast colour,” the dress then worn by the poorest Umbrian peasants, and tied it round him with a knotted rope, Francis went forth at once exhorting the people of the country-side to penance, brotherly love, and peace.

The Assisians had already ceased to scoff at Francis; they now paused in wonderment; his example even drew others to him. Bernard of Quintavalle, a magnate of the town, was the first to join Francis, and he was soon followed by Peter of Cattaneo, a well-known canon of the cathedral. In true spirit of religious enthusiasm, Francis repaired to the church of St. Nicholas and sought to learn God’s will in their regard by thrice opening at random the book of the Gospels on the altar. Each time it opened at passages where Christ told His disciples to leave all things and follow Him. “This shall be our rule of life,” exclaimed Francis, and led his companions to the public square, where they forthwith gave away all their belongings to the poor. After this they procured rough habits like that of Francis, and built themselves small huts near his at the Porziuncola.

A few days later Giles, afterwards the great ecstatic and sayer of “good words,” became the third follower of Francis. The little band divided and went about, two and two, making such an impression by their words and behaviour that before long several other disciples grouped themselves round Francis eager to share his poverty, among them being Sabatinus, vir bonus et justus, Moricus, who had belonged to the Crucigeri, John of Capella, who afterwards fell away, Philip “the Long,” and four others of whom we know only the names.

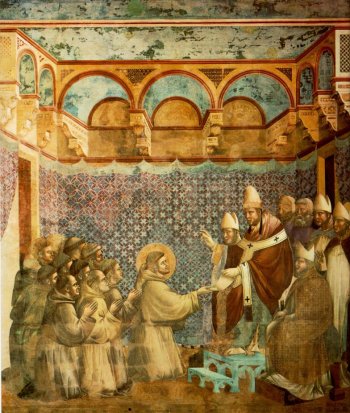

When the number of his companions had increased to eleven, Francis found it expedient to draw up a written rule for them. This first rule,as it is called, of the Friars Minor has not come down to us in its original form, but it appears to have been very short and simple, a mere adaptation of the Gospel precepts already selected by Francis for the guidance of his first companions, and which he desired to practice in all their perfection. When this rule was ready the Penitents of Assisi, as Francis and his followers styled themselves, set out for Rome to seek the approval of the Holy See, although as yet no such approbation was obligatory.

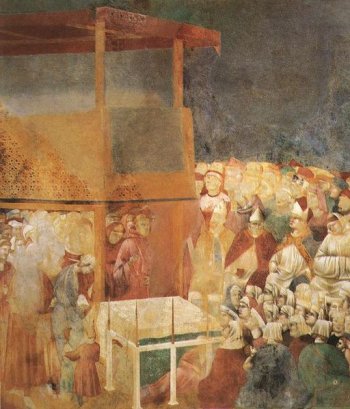

There are differing accounts of Francis’s reception by Innocent III. It seems, however, that Guido, Bishop of Assisi, who was then in Rome, commended Francis to Cardinal John of St. Paul, and that at the instance of the latter, the pope recalled the saint whose first overtures he had, as it appears, somewhat rudely rejected. Moreover, in spite of the sinister predictions of others in the Sacred College, who regarded the mode of life proposed by Francis as unsafe and impracticable, Innocent, moved it is said by a dream in which he beheld the Poor Man of Assisi upholding the tottering Lateran, gave a verbal sanction to the rule submitted by Francis and granted the saint and his companions leave to preach repentance everywhere. Before leaving Rome they all received the ecclesiastical tonsure, Francis himself being ordained deacon later on.

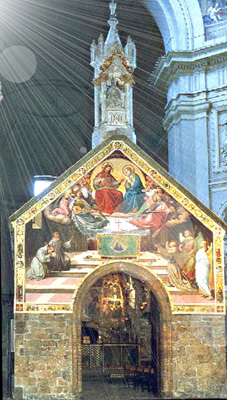

After their return to Assisi, the Friars Minor, for thus Francis had named his brethren–either after the minores, or lower classes, as some think, or as others believe, with reference to the Gospel (Matthew 25:40-45), and as a perpetual reminder of their humility–found shelter in a deserted hut at Rivo Torto in the plain below the city, but were forced to abandon this poor abode by a rough peasant who drove in his ass upon them. About 1211 they obtained a permanent foothold near Assisi, through the generosity of the Benedictines of Monte Subasio, who gave them the little chapel of St. Mary of the Angels or the Porziuncola. Adjoining this humble sanctuary, already dear to Francis, the first Franciscan convent was formed by the erection of a few small huts or cells of wattle, straw, and mud, and enclosed by a hedge.

From this settlement, which became the cradle of the Franciscan Order (Caput et Mater Ordinis) and the central spot in the life of St. Francis, the Friars Minor went forth two by two exhorting the people of the surrounding country. Like children “careless of the day,” they wandered from place to place singing in their joy, and calling themselves the Lord’s minstrels. The wide world was their cloister; sleeping in haylofts, grottos, or church porches, they toiled with the labourers in the fields, and when none gave them work they would beg.

In a short while Francis and his companions gained an immense influence, and men of different grades of life and ways of thought flocked to the order. Among the new recruits made about this time By Francis were the famous Three Companions, who afterwards wrote his life, namely: Angelus Tancredi, a noble cavalier; Leo, the saint’s secretary and confessor; and Rufinus, a cousin of St. Clare; besides Juniper, “the renowned jester of the Lord.”

During the Lent of 1212, a new joy, great as it was unexpected, came to Francis. Clare, a young heiress of Assisi, moved by the saint’s preaching at the church of St. George, sought him out, and begged to be allowed to embrace the new manner of life he had founded. By his advice, Clare, who was then but eighteen, secretly left her father’s house on the night following Palm Sunday, and with two companions went to the Porziuncola, where the friars met her in procession, carrying lighted torches. Then Francis, having cut off her hair, clothed her in the Minorite habit and thus received her to a life of poverty, penance, and seclusion.

Clare stayed provisionally with some Benedictine nuns near Assisi, until Francis could provide a suitable retreat for her, and for St. Agnes, her sister, and the other pious maidens who had joined her. He eventually established them at St. Damian’s, in a dwelling adjoining the chapel he had rebuilt with his own hands, which was now given to the saint by the Benedictines as domicile for his spiritual daughters, and which thus became the first monastery of the Second Franciscan Order of Poor Ladies, now known as Poor Clares.

In the autumn of the same year (1212) Francis’s burning desire for the conversion of the Saracens led him to embark for Syria, but having been shipwrecked on the coast of Slavonia, he had to return to Ancona. The following spring he devoted himself to evangelizing Central Italy. About this time (1213) Francis received from Count Orlando of Chiusi the mountain of La Verna, an isolated peak among the Tuscan Apennines, rising some 4000 feet above the valley of the Casentino, as a retreat, “especially favourable for contemplation,” to which he might retire from time to time for prayer and rest. Francis never altogether separated the contemplative from the active life, as the several hermitages associated with his memory, and the quaint regulations he wrote for those living in them bear witness. At one time, indeed, a strong desire to give himself wholly to a life of contemplation seems to have possessed the saint.

During the next year (1214) Francis set out for Morocco, in another attempt to reach the infidels and, if needs be, to shed his blood for the Gospel, but while yet in Spain was overtaken by so severe an illness that he was compelled to turn back to Italy once more.

Authentic details are unfortunately lacking of Francis’s journey to Spain and sojourn there. It probably took place in the winter of 1214-1215. After his return to Umbria he received several noble and learned men into his order, including his future biographer Thomas of Celano.

The next eighteen months comprise, perhaps, the most obscure period of the saint’s life. That he took part in the Lateran Council of 1215 may well be, but it is not certain; we know from Eccleston, however, that Francis was present at the death of Innocent II, which took place at Perugia, in July 1216. Shortly afterwards, i.e. very early in the pontificate of Honorius III, is placed the concession of the famous Porziuncola Indulgence.

It is related that once, while Francis was praying at the Porziuncola, Christ appeared to him and offered him whatever favour he might desire.The salvation of souls was ever the burden of Francis’s prayers,and wishing moreover, to make his beloved Porziuncola a sanctuary where many might be saved, he begged a plenary Indulgence for all who, having confessed their sins, should visit the little chapel. Our Lord acceded to this request on condition that the pope should ratify the Indulgence. Francis thereupon set out for Perugia, with Brother Masseo, to find Honorius III. The latter, notwithstanding some opposition from the Curia at such an unheard-of favour, granted the Indulgence, restricting it, however, to one day yearly.

He subsequently fixed 2 August in perpetuity, as the day for gaining this Porziuncola Indulgence, commonly known in Italy as il perdono d’Assisi. Such is the traditional account. The fact that there is no record of this Indulgence in either the papal or diocesan archives and no allusion to it in the earliest biographies of Francis or other contemporary documents has led some writers to reject the whole story. This argumentum ex silentio has, however, been met by M. Paul Sabatier, who in his critical edition of the “Tractatus de Indulgentia” of Fra Bartholi has adduced all the really credible evidence in its favour. But even those who regard the granting of this Indulgence as traditionally believed to be an established fact of history, admit that its early history is uncertain.

The first general chapter of the Friars Minor was held in May, 1217, at Porziuncola, the order being divided into provinces, and an apportionment made of the Christian world into so many Franciscan missions. Tuscany, Lombardy, Provence, Spain, and Germany were assigned to five of Francis’s principal followers; for himself the saint reserved France, and he actually set out for that kingdom, but on arriving at Florence, was dissuaded from going further by Cardinal Ugolino, who had been made protector of the order in 1216. He therefore sent in his stead Brother Pacificus, who in the world had been renowned as a poet, together with Brother Agnellus, who later on established the Friars Minor in England.

Although success came indeed to Francis and his friars, with it came also opposition, and it was with a view to allaying any prejudices the Curia might have imbibed against their methods that Francis, at the instance of Cardinal Ugolino, went to Rome and preached before the pope and cardinals in the Lateran. This visit to the Eternal City, which took place 1217-18, was apparently the occasion of Francis’s memorable meeting with St. Dominic.

The year 1218 Francis devoted to missionary tours in Italy, which were a continual triumph for him. He usually preached out of doors, in the market-places, from church steps, from the walls of castle courtyards. Allured by the magic spell of his presence, admiring crowds, unused for the rest to anything like popular preaching in the vernacular, followed Francis from place to place hanging on his lips; church bells rang at his approach; processions of clergy and people advanced to meet him with music and singing; they brought the sick to him to bless and heal, and kissed the very ground on which he trod, and even sought to cut away pieces of his tunic.

The extraordinary enthusiasm with which the saint was everywhere welcomed was equalled only by the immediate and visible result of his preaching. His exhortations of the people, for sermons they can hardly be called, short, homely, affectionate, and pathetic, touched even the hardest and most frivolous, and Francis became in sooth a very conqueror of souls. Thus it happened, on one occasion, while the saint was preaching at Camara, a small village near Assisi, that the whole congregation were so moved by his “words of spirit and life” that they presented themselves to him in a body and begged to be admitted into his order.

It was to accede, so far as might be, to like requests that Francis devised his Third Order, as it is now called, of the Brothers and Sisters of Penance, which he intended as a sort of middle state between the world and the cloister for those who could not leave their home or desert their wonted avocations in order to enter either the First Order of Friars Minor or the Second Order of Poor Ladies.

That Francis prescribed particular duties for these tertiaries is beyond question. They were not to carry arms, or take oaths, or engage in lawsuits, etc. It is also said that he drew up a formal rule for them, but it is clear that the rule, confirmed by Nicholas IV in 1289, does not, at least in the form in which it has come down to us, represent the original rule of the Brothers and Sisters of Penance. In any event, it is customary to assign 1221 as the year of the foundation of this third order, but the date is not certain.

At the second general chapter (May, 1219) Francis, bent on realizing his project of evangelizing the infidels, assigned a separate mission to each of his foremost disciples, himself selecting the seat of war between the crusaders and the Saracens. With eleven companions, including Brother Illuminato and Peter of Cattaneo, Francis set sail from Ancona on 21 June, for Saint-Jean d’Acre, and he was present at the siege and taking of Damietta.

After preaching there to the assembled Christian forces, Francis fearlessly passed over to the infidel camp, where he was taken prisoner and led before the sultan. According to the testimony of Jacques de Vitry, who was with the crusaders at Damietta, the sultan received Francis with courtesy, but beyond obtaining a promise from this ruler of more indulgent treatment for the Christian captives, the saint’s preaching seems to have effected little. Before returning to Europe, the saint is believed to have visited Palestine and there obtained for the friars the foothold they still retain as guardians of the holy places.

What is certain is that Francis was compelled to hasten back to Italy because of various troubles that had arisen there during his absence. News had reached him in the East that Matthew of Narni and Gregory of Naples, the two vicars-general whom he had left in charge of the order, had summoned a chapter which, among other innovations, sought to impose new fasts upon the friars, more severe than the rule required. Moreover, Cardinal Ugolino had conferred on the Poor Ladies a written rule which was practically that of the Benedictine nuns, and Brother Philip, whom Francis had charged with their interests, had accepted it.

To make matters worse, John of Capella, one of the saint’s first companions, had assembled a large number of lepers, both men and women, with a view to forming them into a new religious order, and had set out for Rome to seek approval for the rule he had drawn up for these unfortunates. Finally a rumour had been spread abroad that Francis was dead, so that when the saint returned to Italy with brother Elias–he appeared to have arrived at Venice in July, 1220–a general feeling of unrest prevailed among the friars.

Apart from these difficulties, the order was then passing through a period of transition. It had become evident that the simple, familiar, and unceremonious ways which had marked the Franciscan movement at its beginning were gradually disappearing, and that the heroic poverty practiced by Francis and his companions at the outset became less easy as the friars with amazing rapidity increased in number. And this Francis could not help seeing on his return.

Cardinal Ugolino had already undertaken the task “of reconciling inspirations so unstudied and so free with an order of things they had outgrown.” This remarkable man, who afterwards ascended the papal throne as Gregory IX, was deeply attached to Francis, whom he venerated as a saint and also, some writers tell us, managed as an enthusiast. That Cardinal Ugolino had no small share in bringing Francis’s lofty ideals “within range and compass” seems beyond dispute, and it is not difficult to recognize his hand in the important changes made in the organization of the order in the so-called Chapter of Mats. At this famous assembly, held at Porziuncola at Whitsuntide, 1220 or 1221 (there is seemingly much room for doubt as to the exact date and number of the early chapters), about 5000 friars are said to have been present, besides some 500 applicants for admission to the order. Huts of wattle and mud afforded shelter for this multitude.

Francis had purposely made no provision for them, but the charity of the neighbouring towns supplied them with food, while knights and nobles waited upon them gladly. It was on this occasion that Francis, harassed no doubt and disheartened at the tendency betrayed by a large number of the friars to relax the rigours of the rule, according to the promptings of human prudence, and feeling, perhaps unfitted for a place which now called largely for organizing abilities, relinquished his position as general of the order in favour of Peter of Cattaneo. But the latter died in less than a year, being succeeded as vicar-general by the unhappy Brother Elias, who continued in that office until the death of Francis.

The saint, meanwhile, during the few years that remained in him, sought to impress on the friars by the silent teaching of personal example of what sort he would fain have them to be. Already, while passing through Bologna on his return from the East, Francis had refused to enter the convent there because he had heard it called the “House of the Friars” and because a studium had been instituted there. He moreover bade all the friars, even those who were ill, quit it at once, and it was only some time after, when Cardinal Ugolino had publicly declared the house to be his own property, that Francis suffered his brethren to re-enter it.

Yet strong and definite as the saint’s convictions were, and determinedly as his line was taken, he was never a slave to a theory in regard to the observances of poverty or anything else; about him indeed, there was nothing narrow or fanatical. As for his attitude towards study, Francis desiderated for his friars only such theological knowledge as was conformable to the mission of the order, which was before all else a mission of example. Hence he regarded the accumulation of books as being at variance with the poverty his friars professed, and he resisted the eager desire for mere book-learning, so prevalent in his time, in so far as it struck at the roots of that simplicity which entered so largely into the essence of his life and ideal and threatened to stifle the spirit of prayer, which he accounted preferable to all the rest.

In 1221, so some writers tell us, Francis drew up a new rule for the Friars Minor. Others regard this so-called Rule of 1221 not as a new rule, but as the first one which Innocent had orally approved; not, indeed, its original form, which we do not possess, but with such additions and modifications as it has suffered during the course of twelve years.

However this may be, the composition called by some the Rule of 1221 is very unlike any conventional rule ever made. It was too lengthy and unprecise to become a formal rule, and two years later Francis retired to Fonte Colombo, a hermitage near Rieti, and rewrote the rule in more compendious form. This revised draft he entrusted to Brother Elias, who not long after declared he had lost it through negligence.

Francis thereupon returned to the solitude of Fonte Colombo, and recast the rule on the same lines as before, its twenty-three chapters being reduced to twelve and some of its precepts being modified in certain details at the instance of Cardinal Ugolino. In this form the rule was solemnly approved by Honorius III, 29 November, 1223 (Litt. “Solet annuere”).

This Second Rule, as it is usually called or Regula Bullata of the Friars Minor, is the one ever since professed throughout the First Order of St. Francis. It is based on the three vows of obedience, poverty, and chastity, special stress however being laid on poverty, which Francis sought to make the special characteristic of his order, and which became the sign to be contradicted. This vow of absolute poverty in the first and second orders and the reconciliation of the religious with the secular state in the Third Order of Penance are the chief novelties introduced by Francis in monastic regulation.

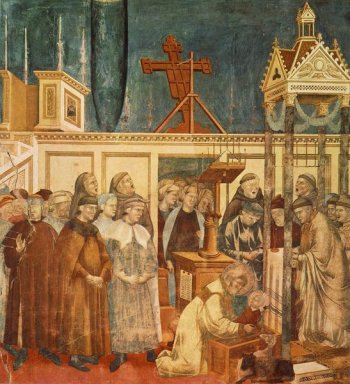

It was during Christmastide of this year (1223) that the saint conceived the idea of celebrating the Nativity “in a new manner,” by reproducing in a church at Greccio the praesepio of Bethlehem, and he has thus come to be regarded as having inaugurated the popular devotion of the Crib. Christmas appears indeed to have been the favourite feast of Francis, and he wished to persuade the emperor to make a special law that men should then provide well for the birds and the beasts, as well as for the poor, so that all might have occasion to rejoice in the Lord.

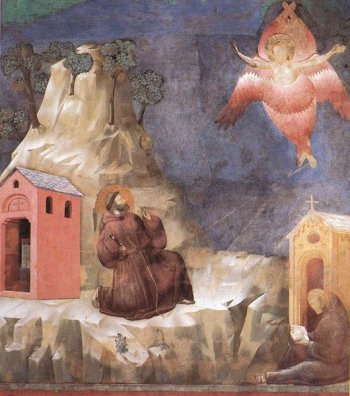

Early in August, 1224, Francis retired with three companions to “that rugged rock ‘twixt Tiber and Arno,” as Dante called La Verna, there to keep a forty days fast in preparation for Michaelmas. During this retreat the sufferings of Christ became more than ever the burden of his meditations; into few souls, perhaps, had the full meaning of the Passion so deeply entered.

It was on or about the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (14 September) while praying on the mountainside, that he beheld the marvellous vision of the seraph, as a sequel of which there appeared on his body the visible marks of the five wounds of the Crucified which, says an early writer, had long since been impressed upon his heart. Brother Leo, who was with St. Francis when he received the stigmata, has left us in his note to the saint’s autograph blessing, preserved at Assisi, a clear and simple account of the miracle, which for the rest is better attested than many another historical fact.

The saint’s right side is described as bearing an open wound which looked as if made by a lance, while through his hands and feet were black nails of flesh, the points of which were bent backward. After the reception of the stigmata, Francis suffered increasing pains throughout his frail body, already broken by continual mortification. For, condescending as the saint always was to the weaknesses of others, he was ever so unsparing towards himself that at the last he felt constrained to ask pardon of “Brother Ass,” as he called his body, for having treated it so harshly. Worn out, moreover, as Francis now was by eighteen years of unremitting toil, his strength gave way completely, and at times his eyesight so far failed him that he was almost wholly blind.

During an access of anguish, Francis paid a last visit to St. Clare at St. Damian’s, and it was in a little hut of reeds, made for him in the garden there, that the saint composed that “Canticle of the Sun,” in which his poetic genius expands itself so gloriously. This was in September, 1225. Not long afterwards Francis, at the urgent instance of Brother Elias, underwent an unsuccessful operation for the eyes, at Rieti.

He seems to have passed the winter 1225-26 at Siena, whither he had been taken for further medical treatment. In April, 1226, during an interval of improvement, Francis was moved to Cortona, and it is believed to have been while resting at the hermitage of the Celle there, that the saint dictated his testament, which he describes as a “reminder, a warning, and an exhortation”. In this touching document Francis, writing from the fullness of his heart, urges anew with the simple eloquence, the few, but clearly defined, principles that were to guide his followers, implicit obedience to superiors as holding the place of God, literal observance of the rule “without gloss,” especially as regards poverty, and the duty of manual labor, being solemnly enjoined on all the friars.

Meanwhile alarming dropsical symptoms had developed, and it was in a dying condition that Francis set out for Assisi. A roundabout route was taken by the little caravan that escorted him, for it was feared to follow the direct road lest the saucy Perugians should attempt to carry Francis off by force so that he might die in their city, which would thus enter into possession of his coveted relics. It was therefore under a strong guard that Francis, in July, 1226, was finally borne in safety to the bishop’s palace in his native city amid the enthusiastic rejoicings of the entire populace.

In the early autumn Francis, feeling the hand of death upon him, was carried to his beloved Porziuncola, that he might breathe his last sigh where his vocation had been revealed to him and whence his order had struggled into sight. On the way thither he asked to be set down, and with painful effort he invoked a beautiful blessing on Assisi, which, however, his eyes could no longer discern.

The saint’s last days were passed at the Porziuncola in a tiny hut, near the chapel, that served as an infirmary. The arrival there about this time of the Lady Jacoba of Settesoli, who had come with her two sons and a great retinue to bid Francis farewell, caused some consternation, since women were forbidden to enter the friary. But Francis in his tender gratitude to this Roman noblewoman, made an exception in her favour, and “Brother Jacoba,” as Francis had named her on account of her fortitude, remained to the last.

On the eve of his death, the saint, in imitation of his Divine Master, had bread brought to him and broken. This he distributed among those present, blessing Bernard of Quintaville, his first companion, Elias, his vicar, and all the others in order. “I have done my part,” he said next, “may Christ teach you to do yours.” Then wishing to give a last token of detachment and to show he no longer had anything in common with the world, Francis removed his poor habit and lay down on the bare ground, covered with a borrowed cloth, rejoicing that he was able to keep faith with his Lady Poverty to the end. After a while he asked to have read to him the Passion according to St. John, and then in faltering tones he himself intoned Psalm cxli. At the concluding verse, “Bring my soul out of prison,” Francis was led away from earth by “Sister Death,” in whose praise he had shortly before added a new strophe to his “Canticle of the Sun”. It was Saturday evening, 3 October, 1226, Francis being then in the forty-fifth year of his age, and the twentieth from his perfect conversion to Christ.

The saint had, in his humility, it is said, expressed a wish to be buried on the Colle d’Inferno, a despised hill without Assisi, where criminals were executed. However this may be, his body was, on 4 October, borne in triumphant procession to the city, a halt being made at St. Damian’s, that St. Clare and her companions might venerate the sacred stigmata now visible to all, and it was placed provisionally in the church of St. George (now within the enclosure of the monastery of St. Clare), where the saint had learned to read and had first preached.

Many miracles are recorded to have taken place at his tomb. Francis was canonized at St. George’s by Gregory IX, 16 July, 1228. On that day following the pope laid the first stone of the great double church of St. Francis, erected in honour of the new saint, and thither on 25 May, 1230, Francis’s remains were secretly transferred by Brother Elias and buried far down under the high altar in the lower church. Here, after lying hidden for six centuries, like that of St. Clare’s, Francis’s coffin was found, 12 December, 1818, as a result of a toilsome search lasting fifty-two nights. This discovery of the saint’s body is commemorated in the order by a special office on 12 December, and that of his translation by another on 25 May. His feast is kept throughout the Church on 4 October, and the impression of the stigmata on his body is celebrated on 17 September.

It has been said with pardonable warmth that Francis entered into glory in his lifetime, and that he is the one saint whom all succeeding generations have agreed in canonizing. Certain it is that those also who care little about the order he founded, and who have but scant sympathy with the Church to which he ever gave his devout allegiance, even those who know that Christianity to be Divine, find themselves, instinctively as it were, looking across the ages for guidance to the wonderful Umbrian Poverello, and invoking his name in grateful remembrance. This unique position Francis doubtless owes in no small measure to his singularly lovable and winsome personality.

Few saints ever exhaled “the good odour of Christ” to such a degree as he. There was about Francis, moreover, a chivalry and a poetry which gave to his other- worldliness a quite romantic charm and beauty. Other saints have seemed entirely dead to the world around them, but Francis was ever thoroughly in touch with the spirit of the age. He delighted in the songs of Provence, rejoiced in the new-born freedom of his native city, and cherished what Dante calls the pleasant sound of his dear land. And this exquisite human element in Francis’s character was the key to that far-reaching, all-embracing sympathy, which may be almost called his characteristic gift.

In his heart, as an old chronicler puts it, the whole world found refuge, the poor, the sick and the fallen being the objects of his solicitude in a more special manner. Heedless as Francis ever was of the world’s judgments in his own regard, it was always his constant care to respect the opinions of all and to wound the feelings of none. Wherefore he admonishes the friars to use only low and mean tables, so that “if a beggar were to come to sit down near them he might believe that he was but with his equals and need not blush on account of his poverty.”

One night, we are told, the friary was aroused by the cry “I am dying.”

“Who are you,” exclaimed Francis arising, “and why are you dying?”

“I am dying of hunger,” answered the voice of one who had been too prone to fasting. Whereupon Francis had a table laid out and sat down beside the famished friar, and lest the latter might be ashamed to eat alone, ordered all the other brethren to join in the repast.

Francis’s devotedness in consoling the afflicted made him so condescending that he shrank not from abiding with the lepers in their loathly lazar-houses and from eating with them out of the same platter. But above all it is his dealings with the erring that reveal the truly Christian spirit of his charity.

“Saintlier than any of the saint,” writes Celano, “among sinners he was as one of themselves”.

Writing to a certain minister in the order, Francis says: “Should there be a brother anywhere in the world who has sinned, no matter how great soever his fault may be, let him not go away after he has once seen thy face without showing pity towards him; and if he seek not mercy, ask him if he does not desire it. And by this I will know if you love God and me.”

Again, to medieval notions of justice the evil-doer was beyond the law and there was no need to keep faith with him. But according to Francis, not only was justice due even to evil-doers, but justice must be preceded by courtesy as by a herald. Courtesy, indeed, in the saint’s quaint concept, was the younger sister of charity and one of the qualities of God Himself, Who “of His courtesy,” he declares, “gives His sun and His rain to the just and the unjust”.

This habit of courtesy Francis ever sought to enjoin on his disciples. “Whoever may come to us,” he writes, “whether a friend or a foe, a thief or a robber, let him be kindly received,” and the feast which he spread for the starving brigands in the forest at Monte Casale sufficed to show that “as he taught so he wrought”.

The very animals found in Francis a tender friend and protector; thus we find him pleading with the people of Gubbio to feed the fierce wolf that had ravished their flocks, because through hunger “Brother Wolf” had done this wrong. And the early legends have left us many an idyllic picture of how beasts and birds alike susceptible to the charm of Francis’s gentle ways, entered into loving companionship with him; how the hunted leveret sought to attract his notice; how the half-frozen bees crawled towards him in the winter to be fed; how the wild falcon fluttered around him; how the nightingale sang with him in sweetest content in the ilex grove at the Carceri, and how his “little brethren the birds” listened so devoutly to his sermon by the roadside near Bevagna that Francis chided himself for not having thought of preaching to them before.

Francis’s love of nature also stands out in bold relief in the world he moved in. He delighted to commune with the wild flowers, the crystal spring, and the friendly fire, and to greet the sun as it rose upon the fair Umbrian vale. In this respect, indeed, St. Francis’s “gift of sympathy” seems to have been wider even than St. Paul’s, for we find no evidence in the great Apostle of a love for nature or for animals.

Hardly less engaging than his boundless sense of fellow-feeling was Francis’s downright sincerity and artless simplicity. “Dearly beloved,” he once began a sermon following upon a severe illness, “I have to confess to God and you that during this Lent I have eaten cakes made with lard.” And when the guardian insisted for the sake of warmth upon Francis having a fox skin sewn under his worn-out tunic, the saint consented only upon condition that another skin of the same size be sewn outside. For it was his singular study never to hide from men that which known to God.

“What a man is in the sight of God,” he was wont to repeat, “so much he is and no more”–a saying which passed into the “Imitation,” and has been often quoted. Another winning trait of Francis which inspires the deepest affection was his unswerving directness of purpose and unfaltering following after an ideal.

“His dearest desire so long as he lived,” Celano tells us, “was ever to seek among wise and simple, perfect and imperfect, the means to walk in the way of truth.”

To Francis love was the truest of all truths; hence his deep sense of personal responsibility towards his fellows. The love of Christ and Him Crucified permeated the whole life and character of Francis, and he placed the chief hope of redemption and redress for a suffering humanity in the literal imitation of his Divine Master. The saint imitated the example of Christ as literally as it was in him to do so; barefoot, and in absolute poverty, he proclaimed the reign of love.

This heroic imitation of Christ’s poverty was perhaps the distinctive mark of Francis’s vocation, and he was undoubtedly, as Bossuet expresses it, the most ardent, enthusiastic, and desperate lover of poverty the world has yet seen.

After money Francis most detested discord and divisions. Peace, therefore, became his watchword, and the pathetic reconciliation he effected in his last days between the Bishop and Potesta of Assisi is bit one instance out of many of his power to quell the storms of passion and restore tranquility to hearts torn asunder by civil strife. The duty of a servant of God, Francis declared, was to lift up the hearts of men and move them to spiritual gladness. Hence it was not “from monastic stalls or with the careful irresponsibility of the enclosed student” that the saint and his followers addressed the people” “they dwelt among them and grappled with the evils of the system under which the people groaned”. They worked in return for their fare, doing for the lowest the most menial labour, and speaking to the poorest words of hope such as the world had not heard for many a day. In this wise Francis bridged the chasm between an aristocratic clergy and the common people, and though he taught no new doctrine, he so far repopularized the old one given on the Mount that the Gospel took on a new life and called forth a new love.

Such in briefest outline are some of the salient features which render the figure of Francis one of such supreme attraction that all manner of men feel themselves drawn towards him, with a sense of personal attachment. Few, however, of those who feel the charm of Francis’s personality may follow the saint to his lonely height of rapt communion with God. For, however engaging a “minstrel of the Lord,” Francis was none the less a profound mystic in the truest sense of the word. The whole world was to him one luminous ladder, mounting upon the rungs of which he approached and beheld God.

It is very misleading, however, to portray Francis as living “at a height where dogma ceases to exist,” and still further from the truth to represent the trend of his teaching as one in which orthodoxy is made subservient to “humanitarianism”. A very cursory inquiry into Francis’s religious belief suffices to show that it embraced the entire Catholic dogma, nothing more or less. If then the saint’s sermons were on the whole moral rather than doctrinal, it was less because he preached to meet the wants of his day, and those whom he addressed had not strayed from dogmatic truth; they were still “hearers,” if not “doers,” of the Word. For this reason Francis set aside all questions more theoretical than practical, and returned to the Gospel.

Again, to see in Francis only the loving friend of all God’s creatures, the joyous singer of nature, is to overlook altogether that aspect of his work which is the explanation of all the rest–its supernatural side. Few lives have been more wholly imbued with the supernatural, as even Renan admits. Nowhere, perhaps, can there be found a keener insight into the innermost world of spirit, yet so closely were the supernatural and the natural blended in Francis, that his very asceticism was often clothed in the guide of romance, as witness his wooing the Lady Poverty, in a sense that almost ceased to be figurative. For Francis’s singularly vivid imagination was impregnate with the imagery of the chanson de geste, and owing to his markedly dramatic tendency, he delighted in suiting his action to his thought.

So, too, the saint’s native turn for the picturesque led him to unite religion and nature. He found in all created things, however trivial, some reflection of the Divine perfection, and he loved to admire in them the beauty, power, wisdom, and goodness of their Creator. And so it came to pass that he saw sermons even in stones, and good in everything. Moreover, Francis’s simple, childlike nature fastened on the thought, that if all are from one Father then all are real kin. Hence his custom of claiming brotherhood with all manner of animate and inanimate objects. The personification, therefore, of the elements in the “Canticle of the Sun” is something more than a mere literary figure.

Francis’s love of creatures was not simply the offspring of a soft or sentimental disposition; it arose rather from that deep and abiding sense of the presence of God, which underlay all he said and did. Even so, Francis’s habitual cheerfulness was not that of a careless nature, or of one untouched by sorrow. None witnessed Francis’s hidden struggles, his long agonies of tears, or his secret wrestlings in prayer. And if we meet him making dumb-show of music, by playing a couple of sticks like a violin to give vent to his glee, we also find him heart-sore with foreboding at the dire dissensions in the order which threatened to make shipwreck of his ideal.

Nor were temptations or other weakening maladies of the soul wanting to the saint at any time. Francis’s lightsomeness had its source in that entire surrender of everything present and passing, in which he had found the interior liberty of the children of God; it drew its strength from his intimate union with Jesus in the Holy Communion.

The mystery of the Holy Eucharist, being an extension of the Passion, held a preponderant place in the life of Francis, and he had nothing more at heart than all that concerned the cultus of the Blessed Sacrament. Hence we not only hear of Francis conjuring the clergy to show befitting respect for everything connected with the Sacrifice of the Mass, but we also see him sweeping out poor churches, questing sacred vessels for them, and providing them with altar-breads made by himself. So great, indeed, was Francis’s reverence for the priesthood, because of its relation to the Adorable Sacrament, that in his humility he never dared to aspire to that dignity.

Humility was, no doubt, the saint’s ruling virtue. The idol of an enthusiastic popular devotion, he ever truly believed himself less than the least. Equally admirable was Francis’s prompt and docile obedience to the voice of grace within him, even in the early days of his ill-defined ambition, when the spirit of interpretation failed him. Later on, the saint, with as clear as a sense of his message as any prophet ever had, yielded ungrudging submission to what constituted ecclesiastical authority. No reformer, moreover, was ever, less aggressive than Francis. His apostolate embodied the very noblest spirit of reform; he strove to correct abuses by holding up an ideal. He stretched out his arms in yearning towards those who longed for the “better gifts”. The others he left alone.

And thus, without strife or schism, God’s Poor Little Man of Assisi became the means of renewing the youth of the Church and of imitating the most potent and popular religious movement since the beginnings of Christianity. No doubt this movement had its social as well as its religious side. That the Third Order of St. Francis went far towards re-Christianizing medieval society is a matter of history. However, Francis’s foremost aim was a religious one. To rekindle the love of God in the world and reanimate the life of the spirit in the hearts of men–such was his mission. But because St. Francis sought first the Kingdom of God and His justice, many other things were added unto him. And his own exquisite Franciscan spirit, as it is called, passing out into the wide world, became an abiding source of inspiration. Perhaps it savours of exaggeration to say, as has been said, that “all the threads of civilization in the subsequent centuries seem to hark back to Francis,” and that since his day “the character of the whole Roman Catholic Church is visibly Umbrian”.

It would be difficult, none the less, to overestimate the effect produced by Francis upon the mind of his time, or the quickening power he wielded on the generations which have succeeded him. To mention two aspects only of his all-pervading influence, Francis must surely be reckoned among those to whom the world of art and letters is deeply indebted. Prose, as Arnold observes, could not satisfy the saint’s ardent soul, so he made poetry. He was, indeed, too little versed in the laws of composition to advance far in that direction. But his was the first cry of a nascent poetry which found its highest expression in the “Divine Comedy”; wherefore Francis has been styled the precursor of Dante.

What the saint did was to teach a people “accustomed to the artificial versification of courtly Latin and Provencal poets, the use of their native tongue in simple spontaneous hymns, which became even more popular with the Laudi and Cantici of his poet-follower Jacopone of Todi”. In so far, moreover, as Francis’s repraesentatio, as Salimbene calls it, of the stable at Bethlehem is the first mystery-play we hear of in Italy, he is said to have borne a part in the revival of the drama.

However this may be, if Francis’s love of song called forth the beginnings of Italian verse, his life no less brought about the birth of Italian art. His story, says Ruskin, became a passionate tradition painted everywhere with delight. Full of colour, dramatic possibilities, and human interest, the early Franciscan legend afforded the most popular material for painters since the life of Christ. No sooner, indeed did Francis’s figure make an appearance in art than it became at once a favourite subject, especially with the mystical Umbrian School. So true is this that it has been said we might by following his familiar figure “construct a history of Christian art, from the predecessors of Cimabue down to Guido Reni, Rubens, and Van Dyck”.

Probably the oldest likeness of Francis that has come down to us is that preserved in the Sacro Speco at Subiaco. It is said that it was painted by a Benedictine monk during the saint’s visit there, which may have been in 1218. The absence of the stigmata, halo, and title of saint in this fresco form its chief claim to be considered a contemporary picture; it is not, however, a real portrait in the modern sense of the word, and we are dependent for the traditional presentment of Francis rather on artists’ ideals, like the Della Robbia statue at the Porziuncola, which is surely the saint’s vera effigies, as no Byzantine so-called portrait can ever be, and the graphic description of Francis given by Celano (Vita Prima, c.lxxxiii). Of less than middle height, we are told, and frail in form, Francis had a long yet cheerful face and soft but strong voice, small brilliant black eyes, dark brown hair, and a sparse beard. His person was in no way imposing, yet there was about the saint a delicacy, grace, and distinction which made him most attractive.

The literary materials for the history of St. Francis are more than usually copious and authentic. There are indeed few if any medieval lives more thoroughly documented. We have in the first place the saint’s own writings. These are not voluminous and were never written with a view to setting forth his ideas systematically, yet they bear the stamp of his personality and are marked by the same unvarying features of his preaching. A few leading thoughts taken “from the words of the Lord” seemed to him all sufficing, and these he repeats again and again, adapting them to the needs of the different persons whom he addresses.

Short, simple, and informal, Francis’s writings breathe the unstudied love of the Gospel and enforce the same practical morality, while they abound in allegories and personification and reveal an intimate interweaving of Biblical phraseology. Not all the saint’s writings have come down to us, and not a few of these formerly attributed to him are now with greater likelihood ascribed to others.

The extant and authentic opuscula of Francis comprise, besides the rule of the Friars Minor and some fragments of the other Seraphic legislation, several letters, including one addressed “to all the Christians who dwell in the whole world,” a series of spiritual counsels addressed to his disciples, the “Laudes Creaturarum” or “Canticle of the Sun,” and some lesser praises, an Office of the Passion compiled for his own use, and few other orisons which show us Francis even as Celano saw him, “not so much a man’s praying as prayer itself”.

In addition to the saint’s writings the sources of the history of Francis include a number of early papal bulls and some other diplomatic documents, as they are called, bearing upon his life and work. Then come the biographies properly so called. These include the lives written 1229-1247 by Thomas of Celano, one of Francis’s followers; a joint narrative of his life compiled by Leo, Rufinus, and Angelus, intimate companions of the saint, in 1246; and the celebrated legend of St. Bonaventure, which appeared about 1263; besides a somewhat more polemic legend called the “Speculum Perfectionis,” attributed to Brother Leo, the sate of which is a matter of controversy.

There are also several important thirteenth- century chronicles of the order, like those of Jordan, Eccleston, and Bernard of Besse, and not a few later works, such as the “Chronica XXIV. Generalium” and the “Liber de Conformitate,” which are in some sort a continuation of them. It is upon these works that all the later biographies of Francis’s life are based.

Sources: Text taken entirely from “The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913,” which is in the public domain. The images of the paintings by Francisco de Zurbaran and Giotto are in the public domain. Image of the statue of St. Francis and the Wolf of Gubbio (c) Renardeau. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this image under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version.